How Climate Migration is Forcing a Global Wake-Up Call.

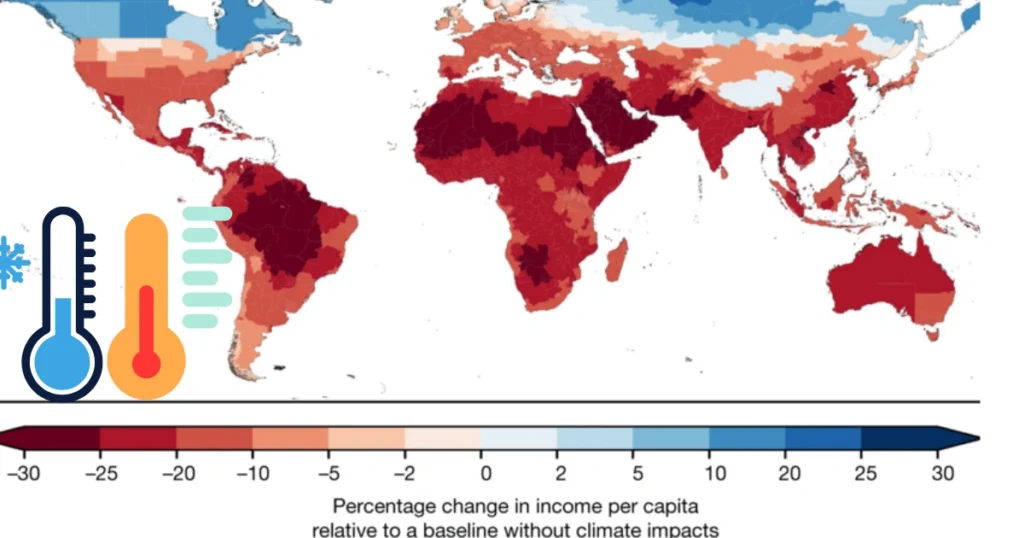

A world map showing projected income decline across regions due to climate change—highlighting areas likely to face climate-driven displacement.

On a sun-scorched afternoon in southern Bangladesh, where rising tides regularly breach embankments and farmland turns to salt, a family of five loads their remaining belongings onto a truck headed north. Their destination? Dhaka—a city already bursting at the seams with over 20 million people. Their story is not unique. It’s part of a sweeping, often invisible shift that’s now shaping the world: climate migration.

The world map, once drawn by wars, treaties, and economic ambitions, is now quietly being reshaped by floods, droughts, wildfires, and hurricanes. From low-lying islands in the Pacific to parched stretches of Sub-Saharan Africa, millions are being uprooted—not by choice, but by necessity.

Table of Contents

The Age of Climate Migration Has Already Begun

For years, policymakers treated climate migration as a future concern—a scenario forecasted for 2050 or beyond. But the numbers say otherwise. According to the World Bank’s Groundswell Report, over 216 million people could be internally displaced by climate-related factors by 2050. That’s nearly the population of Brazil.

But this isn’t just about long-term projections. Right now, entire communities are already on the move. In 2023 alone, over 32 million people were displaced by climate-related disasters, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). Unlike traditional migration, which is often driven by economic opportunity or conflict, climate migration is survival migration. And it’s accelerating.

Where Are People Going—And Why?

Patterns of movement are beginning to reveal a consistent trend: rural to urban, coastal to inland, developing to developed. In sub-Saharan Africa, severe droughts are pushing nomadic herders into already stressed cities like Lagos and Nairobi. In Central America, recurring hurricanes and crop failure are forcing thousands to head north, often toward the U.S. border.

The U.S. itself is not immune. In states like Louisiana and Florida, sea level rise and stronger hurricanes have made entire communities unlivable. The town of Isle de Jean Charles in Louisiana became America’s first federally funded climate relocation zone—a precedent that may become more common.

Meanwhile, Europe is grappling with climate-linked migration from North Africa, where desertification is making agricultural livelihoods impossible. Southern Italy, Greece, and Spain are not only destinations but also battlegrounds for the political questions migration inevitably stirs.

Climate Borders: A New Form of Geopolitics

Climate migration isn’t just shifting people—it’s shifting power. Countries that are better positioned geographically and economically are becoming magnets for displaced populations. But with this movement comes geopolitical tension.

Consider the Indo-Bangladesh border, where increased migration from Bangladesh due to sea-level rise has led India to fortify its borders with more fencing and surveillance. In the U.S., political debate over southern border crossings now increasingly references climate as a “push factor”—a fact rarely acknowledged two decades ago.

And then there’s the Arctic. As warming opens up new shipping routes and access to resources, countries like Russia, the U.S., and Canada are jostling for control. In a twist of irony, while some are being displaced by climate change, others are racing to capitalize on it.

The Human Cost Behind the Statistics

It’s easy to cite figures and projections. Harder is to grasp the human toll behind them. In Kenya’s Turkana region, prolonged droughts have decimated livestock, turning once-proud herders into urban laborers. In Jakarta, Indonesia—one of the fastest-sinking cities in the world—families are abandoning homes passed down through generations.

Even in developed nations, the trauma is real. After the 2018 Camp Fire in California destroyed Paradise, thousands of residents relocated permanently. Many never returned. Insurance markets collapsed. Schools and hospitals downsized. The town’s identity was, in a real sense, erased.

Climate migration, then, is not merely a movement of bodies—it’s a displacement of culture, memory, and belonging.

Global Responsibility in an Uneven Crisis

Here lies the irony: those who contribute least to climate change are the ones most affected by it. Pacific island nations like Tuvalu and Kiribati are facing existential threats, yet their combined carbon footprint is negligible.

In response, some countries are exploring legal frameworks for climate refugee status—a term not currently recognized under the 1951 Refugee Convention. In 2020, the UN made a landmark ruling that people fleeing climate disasters cannot be returned to their country if their lives are at risk.

Still, many wealthy nations remain reluctant to adapt immigration policy for climate reasons. The tension is palpable: do nations have a moral obligation to open their borders to climate migrants? Or will they double down on nationalism, building “climate walls” to protect their own?

India’s Emerging Role

India, too, finds itself at a complex intersection of this crisis. It faces internal climate migration—from rural Bihar and Odisha to megacities like Delhi and Mumbai—as well as potential external pressure from neighbors like Bangladesh.

As the world’s most populous country and a frontline state in the climate crisis, India’s climate migration strategy could shape regional stability. It has an opportunity to lead—by investing in resilient infrastructure, cross-border cooperation, and human-centric climate policies.

(Also Read:https:https://newslyy.com/2025/06/18/brics-challenging-us-dollar-2025/ )

Reimagining the Map, Rethinking the Future

What happens when places once considered home become unlivable? When maps no longer reflect political borders, but climatic ones?

This is not a question for future generations—it’s a challenge for ours. Climate migration is not a passing trend or a one-time disruption. It is a structural transformation, a human redrawing of the globe in real time.

In this new world, success will not belong to the most powerful nations, but to the most prepared ones—those that recognize mobility not as a threat, but as an inevitable feature of a warming planet.

External Source:

World Bank Groundswell Report on Climate Migration

1 thought on “How Climate Migration is Forcing a Global Wake-Up Call.”